This is the second in a three-part series on the use of articulatory gestures in literacy instruction. If you missed the first, see Articulatory gestures in literacy instruction: Part 1- the theoretical rationale. And up next: Part 3- what now?

First, we will look at studies of this approach as incorporated into interventions for students needing extra support in literacy, and later we’ll get to studies of typically-developing young children.

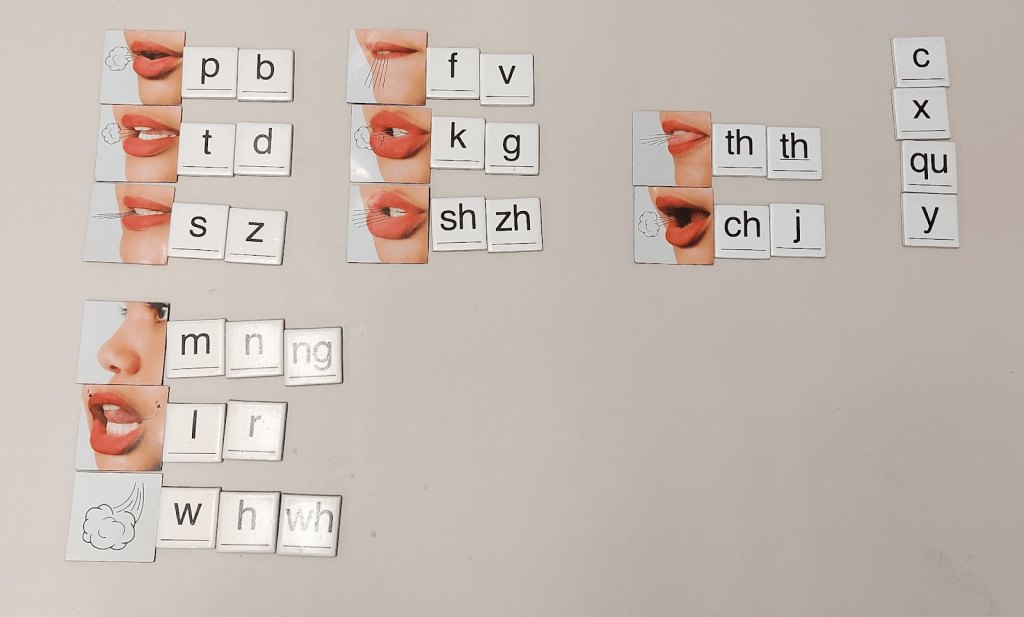

Auditory Discrimination in Depth (ADD), later revised and renamed the Lindamood Phoneme Sequencing Program (LiPS), is a program that makes extensive reference to articulatory gestures, as an intervention for struggling readers (Lindamood & Lindamood, 1975 & 1998). This program calls students’ attention to their articulatory gestures, and demonstrates the sequence of sounds in syllables using coloured blocks, and then links to actual word reading. Consonant phonemes are labelled with friendly terms like “tip tappers” for /t/ and /d/, presented in pairs of voiced and voiceless sounds referred to as “brothers.” Vowel phonemes are presented in a “vowel circle,” arranged by tongue height and backness. Though the focus on speech articulation is what sets ADD/LiPS apart from other programs, it is only one aspect, and this program also follows a systematic, cumulative sequence of instruction in decoding. So, does it work?

Torgesen and colleagues studied the effectiveness of two approaches for children with weak phonological skills: ADD/LiPS and another less explicit approach, with both groups benefiting from 88 hours of one-on-one intervention from mid-Kindergarten through to second grade. The less explicit approach, called embedded phonics (EP) involved children learning whole words by drill, then learning letter-sound correspondence for letters from the drilled words, and writing and reading sentences with these words, with focus on phonemic segmenting during the writing task. At the end of grade two, though both groups made good gains, the ADD/LiPS group outperformed the EP group (Torgesen et al., 1999). But, the groups differed not only in the type of phonemic awareness instruction they received, they differed drastically in the amount of time devoted to phonemic awareness and decoding: 74% of instructional time for children in the ADD/LiPS condition, versus 26% in the less explicit condition. The authors suggest that it’s not possible to determine whether the nature of the activities or the intensity of explicit instruction (three times more focus on phonemic awareness and decoding) was responsible for the advantage seen for the ADD/LiPS group (Torgesen et al., 1999).

Torgesen and colleagues again studied the effects of ADD/LiPS versus a more developed version of their embedded phonics (EP), with additional phonics and phonemic awareness, so that time on foundational skills was the same across conditions. Children aged 8-10 with severe reading disabilities received two 50-minute one-on-one intervention sessions per day over 8 weeks (a remarkably high “dose” of interventions). Results showed that students from both conditions made very good gains in reading, and gains were still evident two years after the 8 weeks of interventions. However, there was no difference between the two groups on measures of word reading, nonword decoding, or passage reading accuracy, fluency, or comprehension, neither immediately after interventions, nor two years later (Torgesen et al., 2001), suggesting that focus on articulatory gestures did not yield an advantage. Somewhat confusingly, this study is often cited as support for the use of articulatory gestures.

A variation on the ADD/LiPS program that incorporated computer activities was compared to Read, Write and Type (RWT), a computer-assisted program from the late 1990s that provides explicit instruction in foundational literacy (without incorporation of articulatory gestures), targeted primarily through written expression. The study looked at 104 first grade students at risk of reading difficulties who received four 50-minute small group session per week, from October to May of first grade. While both groups made good gains compared to controls, there was no significant advantage for children in ADD group compared to the RWT group. Additionally, the authors pointed out that the ADD/LiPS program was much more difficult for teachers to learn and administer (Torgesen et al., 2018).

Borrowing some procedures from ADD/LiPS, Wise and colleagues studied the effect of explicit instruction in articulatory gestures. Three groups of second- to fifth-grade students with reading difficulties participated in interventions that varied in the amount of focus on articulation, but the time spent on phonemic awareness and decoding instruction was the same for all three groups. One group targeted phonological awareness by manipulating blocks and reading/spelling words. Another group focused heavily on articulation, without traditional phonemic awareness activities. A third group did a mix of both, and all three groups received identical phonics instruction. After 50 hours, all groups made good gains on all tests of reading, compared to controls, and gains were sustained 10 months later. Remarkably, the three groups did not differ from each other on any measure of reading, i.e. there was no advantage (or disadvantage) to focusing on articulatory gestures. The authors suggest that there appears to be flexibility in exactly how these concepts are taught (Wise et al., 1999).

Researchers in France studied the outcomes of 19 children aged 7-10 with moderate to severe dyslexia. Joly-Pottuz and colleagues randomly assigned participants into two groups. One group received three weeks of auditory-phonological training and then three weeks of auditory-phonological with articulation training and the second group received the same trainings, in reverse order. Outcomes were measure before, between, and after the two training periods. The auditory-phonological training consisted of listening to pre-recorded phonological awareness tasks (e.g. find the word with the same common middle syllable: député – carburant – débutant) that increased in difficulty over the course of the training period. There was no feedback on performance, and no link to written words. The articulation training involved two activities: learning the place of articulation and voicing for stop sounds (/p, b, t, d, k, g/) and a set of computerized games that further taught voicing contrasts for consonant pairs (e.g., /p, b/, /f, v/). Both groups showed gains in all measure of reading over the six weeks. Of interest: following the articulation training, both groups made better gains in phonological awareness and nonword reading (compared to gains seen following the auditory-phonological training), and one group made better gains on word reading. However, there was no effect of the type of training on spelling (Joly-Pottuz et al., 2008). This study suggests that learning some consonant places of articulation and voicing contrasts was helpful for these students with dyslexia.

In 2014, Trainin and colleagues examined 53 third-grade students reading below grade level, participating in two different interventions: WordWork (Calfee & Patrick, 1995) which included focus on how speech sounds are produced, and Phonological Awareness Training for Reading (Torgesen & Bryant, 1993), with much less emphasis on speech articulation. Interventions were in small groups, over three 45-minute sessions per week, for 11 weeks. After the interventions, the WordWork students performed better on spelling, decoding, and reading fluency compared to the other intervention group (though they did not show stronger phonemic awareness). However, WordWorks differed from the control intervention in other important ways, for example emphasizing instruction in morphology (e.g., suffixes, doubling rule as in tap/tapping, tape/taping), versus the other condition, which focused heavily on oral-only phonemic awareness activities. The authors suggest that teaching a combination of metaphonics, articulation, and orthography in WordWork resulted in superior gains (Trainin et al., 2014), thus this study does not speak to role of articulation specifically.

Swedish researchers aimed to study the effect of a FonoMix, a commercially-available phonological training that includes emphasis on articulation, similar to ADD/LiPS with mouth pictures, but in Swedish. Thirty-nine 6-year-olds participated in the experimental condition, while 30 children served as a comparison group. The children had not yet begun formal literacy instruction, which is customarily introduced at age 7 in Sweden. Children in the the experimental group showed stronger gains in letter names and sounds, word and nonword reading. Students who were at-risk showed particularly good benefit. However, it is not possible to conclude what aspect of FonoMix led to the gains, given that the comparison groups were taught using “whole language” inspired materials and procedures (Fälth et al., 2017), suggesting they lacked explicit teaching of foundational skills. Another study of FonoMix looked at the outcomes of 38 Grade 1 students, randomly assigned to receive either FonoMix interventions condensed into 4-5 weeks or regular classroom instruction. Again, students in the intervention condition made good gains, but the components of the regular classroom instruction were not specified, so it is difficult to draw conclusions about what contributed to the progress of the experimental group (Fälth et al., 2020).

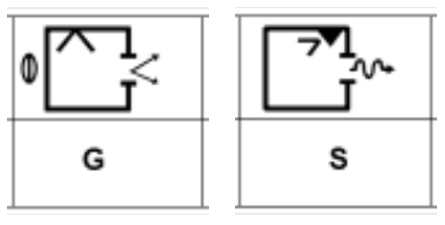

More recently, Norwegian researchers conducted a randomized control trial investigating the effect of articulation training for at-risk grade one students (Thurmann-Moe et al., 2021). A sample of 129 first graders with weak phonological processing abilities were randomly assigned to an intervention condition or a control condition, where students received their schools’ usual interventions. Children in the experimental condition received 20 sessions of 40 minutes, in small groups, focusing on exploring their own articulation using mirrors, learning a symbol system that represents the features of Norwegian speech sounds (see example figure below). They then used these symbols to read and spell words, and practiced transferring to Norwegian orthography. Although the children were able to learn the articulation symbols, there was no difference in their performance on any of the reading or phonological awareness measures, compared to controls. However, there were a number of limitations, including that interventions took place over the last 11 weeks of the school year, and there was perhaps insufficient time to apply their learning to real reading and spelling.

So far we have seen studies that focused on children requiring literacy interventions, and none has made a compelling case for incorporating articulatory gestures. Now we will look at two studies of typically-developing beginning readers. Reading researcher Linnea Ehri published two studies with colleagues in 2003 and 2011 that are very often cited as support for incorporating articulatory gestures into early literacy instruction (Castiglioni-Spalten & Ehri, 2003; Boyer and Ehri, 2011). We should understand the details of these studies, in order to draw conclusions about the practical implications.

The 2003 study involved 45 Kindergarteners who were assigned to three conditions: ear condition, mouth condition, and control condition. Under the ear condition, the children were taught to segment words into phonemes using blocks with a picture of an ear, to cue them to pay attention to the sounds in words. Under the mouth condition, children learned to segment words into phonemes, using blocks with pictures of eight different mouth positions, depicting 13 consonant sounds and three vowel sounds. For example, /t, d, l, n/ were all represented by the same picture of an open mouth and tongue tip lifted to the alveolar ridge. The three vowel sounds included were long E, long A, and long O. Prior to segmenting words, the children in ear and mouth conditions were taught the correspondences between the blocks and the phonemes in words. The children in the mouth condition were taught the correspondence of the mouth pictures to phonemes, using a mirror and discussing their own production of these sounds. The control group participated in regular Kindergarten instruction, where reading was not formally taught.

After six sessions of instruction, the ear and mouth groups performed equally on segmenting words and invented spelling, but both outperformed controls. Experimenters looked at the transfer of these skills to reading of novel words that contained taught sounds, and again there was no advantage for the mouth group. However, the mouth group did outperform both the ear and control groups, when considering how many words were read partially correctly (i.e., a post-hoc analysis, e.g., reading feel as “feet” would be partially correct). The authors concluded that phonemic awareness training was successful for both methods, with and without attention to articulatory gestures. They suggested that “articulatory training facilitated the graphophonemic, connection-forming process that is involved in bonding spellings to phonological representations of words to secure them in memory,” based on the advantage for the mouth group’s ability to read words partially correctly. The authors indicated that findings were suggestive, and could not conclusively inform instructional practices.

The 2011 study by Boyer and Ehri studied 60 preschoolers aged 4-5, split into three groups. The two treatment groups were taught to segment words into phonemes using tiles with letters only (LO), versus letter tiles plus pictures of articulatory gestures (LPA), using the same pictures as the 2003 study. Again, a third control group received regular preschool teaching. Children in the LO and LPA conditions were taught letter-sound correspondences for the 15 letters, and were taught to segment words using letter tiles to represent the phonemes in words. In the LPA condition, children were additionally taught to segment words using the mouth pictures. Children participated until they reached preset criteria for letter naming and phoneme segmenting, which took 4-11 sessions.

Children in both the LO and LPA conditions performed better than controls on all outcome measures of reading, spelling, and phonemic awareness, suggesting both conditions were effective, both one day and seven days later. Children in the LPA condition were able match mouth pictures to their corresponding sounds, whereas the LO group was not, indicating that they learned articulatory awareness from this kind of instruction. To assess specifically the contribution of learning the mouth pictures, the outcomes of the LO and LPA groups were compared. There was no significant difference in these groups’ nonword spelling, number of sounds spelled correctly, recall of the words taught during the training period, number of phonemes segmented (in a phoneme segmenting task using blank tiles), or nonwords repetition (phonological memory), after one week. On the other hand, children in the LPA group outperformed their LO peers on some measures one week after the training. The LPA children were able to segment more words correctly (an average of 3.6/14 words for LO versus 5.1/14 for LPA). Further, on a word-learning task, where children received up to eight trials to learn to read six new words made of taught sounds, the LPA group required fewer trials to learn to read the words, and one week later were able to read significantly more words than the LO group. However, both groups performed the same on spelling of the learned words.

Boyer and Ehri concluded that the addition of teaching articulatory gestures boosted children’s word learning in this study. Given that study participants were 4- and 5-year-olds in the early stages of literacy acquisition, with large vocabularies, from mid-upper socioeconomic status families, the authors indicated that it remained to be investigated whether findings can be generalized to other circumstances; how exactly articulatory gestures should be incorporated into reading instruction was suggested to be a question for further research (Boyer & Ehri, 2011).

A more recent 2021 study examined the effect of a collaborative approach to instruction with a group of 17 preschoolers, over a period of seven weeks. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) worked with a classroom teacher to provide instruction that included articulation placement, phoneme segmentation, letter-sound knowledge, word and nonword decoding, and phoneme segmentation using mouth pictures and letters. Children who had difficulty were seen for small group instruction with the SLP. Prior to the collaboration, the usual classroom practice involved daily thematic stories with some phonics infused, but without explicit phonemic awareness instruction. The researchers measured children’s phoneme segmentation and word reading at three times: at baseline, after seven weeks of usual classroom instruction, and after seven weeks of the collaborative instruction. The children made no gains on these measures after seven weeks of the usual instruction, and impressive gains on all measures after seven weeks of the SLP-teacher collaboration, suggesting that the SLP and teacher were able to work collaboratively to improve early literacy instruction. However, it is not possible to know what elements of the systematic instruction in the classroom were responsible for the children’s growth, not to mention the additional small-group support with the SLP.

And finally, a very recent study was the first to clearly examine the role of attention to articulation in the learning of letter-sound correspondences. Five preschoolers who did not know any letter-sound correspondences and had no developmental concerns were taught the letter-sound correspondences by explicit teaching using flashcards, in twice-daily 5-minute sessions, for about 36 days. Researchers compared the children’s ability to learn letter-sounds under two experimental conditions: with the researcher wearing a blue procedural face mask (as was commonplace during the Covid-19 pandemic), versus without a face mask. In the masked condition, the researcher cued the children to listen to the sound, pointing to her ear before presenting the sound and letter. In the no-mask condition, children were instead prompted to look to the researcher’s mouth, though there was no explicit discussion of the speech gestures. Children were able to learn the letter-sounds in both conditions, but were able to master them after much less instructional time when the researcher was not masked and they were cued to look to her mouth (Novelli et al., 2023). This study suggests that simply being cued to look at a teacher’s mouth may help children make the links between sounds and letters.

That about summarizes the research evidence for articulatory gestures in literacy instruction, but if I have missed any, please do share. While some studies show promise for this approach, they are few, their findings have not yet been replicated, and the instructional implications are often limited, given that the studies often do not look at the contribution of the focus on articulatory gestures specifically. And importantly, the findings do not necessarily reflect what is seen in some current trends. So, what do we do with all of this information? That is the big question and different people will have different ideas about how to proceed. Next time, I will share my view on how we may translate the theory and research to practice.

References:

Becker, R., & Sylvan, L. (2021). Coupling Articulatory Placement Strategies With Phonemic Awareness Instruction to Support Emergent Literacy Skills in Preschool Children: A Collaborative Approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(2), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_LSHSS-20-00095

Boyer, N., & Ehri, L. C. (2011). Contribution of Phonemic Segmentation Instruction With Letters and Articulation Pictures to Word Reading and Spelling in Beginners. Scientific Studies of Reading, 15(5), 440–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2010.520778

Castiglioni-Spalten, M. L., & Ehri, L. C. (2003). Phonemic Awareness Instruction: Contribution of Articulatory Segmentation to Novice Beginners’ Reading and Spelling. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0701_03

Fälth, L., Gustafson, S., & Svensson, I. (2017). Phonological awareness training with articulation promotes early reading development. Education, 137(3), 261–276.

Fälth, L., Svensson, E., & Ström, A. (2020). Intensive Phonological Training With Articulation—An Intervention Study to Boost Pupils’ Word Decoding in Grade 1. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 19(2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1891/JCEP-D-20-00015

Joly-Pottuz, B., Mercier, M., Leynaud, A., & Habib, M. (2008). Combined auditory and articulatory training improves phonological deficit in children with dyslexia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(4), 402–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010701529341

Lindamood, C. H., & Lindamood, P. C. (1975). The ADD Program: Auditory discrimination in depth. (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Lindamood, C. H., & Lindamood, P. C. (1998). The Lindamood phoneme sequencing® program for reading, spelling, and speech. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Novelli, C., Ardoin, S. P., & Rodgers, D. B. (2023). Seeing the mouth: The importance of articulatory gestures during phonics training. Reading and Writing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10487-3

Thurmann-Moe, A. C., Melby-Lervåg, M., & Lervåg, A. (2021). The impact of articulatory consciousness training on reading and spelling literacy in students with severe dyslexia: An experimental single case study. Annals of Dyslexia, 71(3), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-021-00225-1

Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A., Wagner, R. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities.

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Rose, E., Lindamood, P., Conway, T., & Garvan, C. (1999). Preventing Reading Failure in Young Children With Phonological Processing Disabilities: Group and Individual Responses to Instruction.

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., & Herron, J. (2018). Summary of Outcomes from First grade Study with Read, Write, and Type and Auditory Discrimination in Depth instruction and software with at-risk children. Florida Centre of Reading Research.

Trainin, G., Wilson, K. M., Murphy-Yagil, M., & Rankin-Erickson, J. L. (2014). Taking a Different Route: Contribution of Articulation and Metacognition to Intervention With At-Risk Third-Grade Readers. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 19(3–4), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.972103

Wise, B. W., Ring, J., & Olson, R. K. (1999). Training Phonological Awareness with and without Explicit Attention to Articulation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72(4), 271–304. https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1999.2490

Hi, I just wanted to say thank you for this informative series of blog posts, especially Part 2. a great synopsis of the available research on articulatory gestures in literacy instruction!

LikeLiked by 1 person

slick! Reports Highlight [Economic Trends] Affecting [Region] 2025 sharp

LikeLike