Updated November 26, 2022

Once we know how to read, we read fast, recognizing a word in a fraction of a second. In fact, for most people, reading is not just easy, it’s automatic. You can’t stop yourself from reading words that you see; they just jump off of the page and into your brain (and out of your mouth if you’re reading out loud). Here is a little demo. Try to quickly say aloud the colour of the font for each word.

red — orange — green — blue — purple — brown

purple — blue — red — orange — brown — green

The Stroop effect is a classic demonstration of how our brains automatically process written words. Did you hesitate on the words in the second set? Maybe you even blurted out “purple” by mistake for the first word? It’s harder to say the colour of the font in the second line, because reading is so automatic for your brain that it overrides colour recognition. This can seem a little counterintuitive. After all, kids learn their colours before they learn to read words, so shouldn’t colour recognition be a simpler and therefore likely a faster job? Clearly, there is something special about the way the brain processes written words so efficiently. But kids obviously don’t start out reading so efficiently, so how do we get there?

The best current answer to this is through orthographic mapping, the process by which we store written words in our long-term memory, for quick retrieval at a later time. This concept was first described by Linnea Ehri, who explains it as creating links that “glue” spelling to the pronunciation of words in long-term memory. To create these links, we need to be very good at two things:

- breaking spoken words down into sounds (phonemic awareness)

- knowing which sounds can be represented by which letters (letter-sound knowledge)

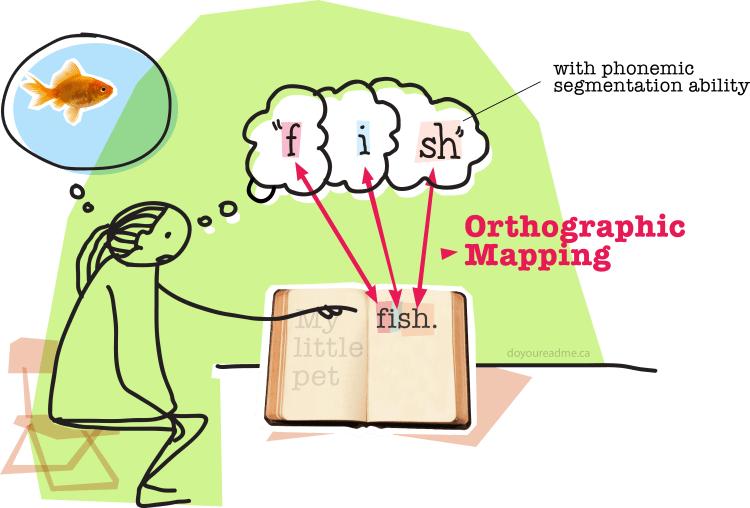

Here, a child encounters the word “fish” and attends to the sounds and the letters in the entire word. This child has good phonemic awareness: she knows that there are individual sounds in the spoken word and so is able to create strong links between the sounds and the letters.

Unfortunately, some children get stuck for a long time in the stage where they slowly, labouriously sound out words, or where they are relying on cues from the context to help them read words. Sometimes, these are children with a learning disability called dyslexia (also called Specific Learning Disorder in reading- word recognition, decoding, and spelling). One of the hallmarks of dyslexia is poor phonemic awareness, leading to poor orthographic mapping, and slow, inaccurate reading.

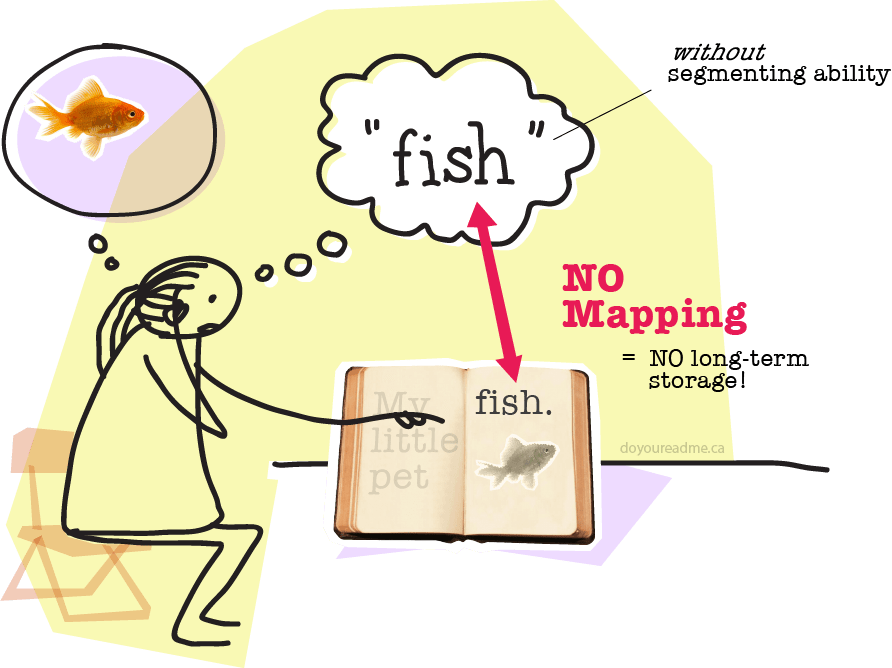

Here, the child has correctly figured out the word “fish” but has not made the links between the pronunciation and the spelling of the word, because the individual sounds within the word “f-i-sh” are not obvious to her. Perhaps she figured out the word by looking at the first letter, by thinking about what word would make sense in the sentence, by looking at the picture, or by some combination of these clues. Children who read this way may read simple texts accurately, but will not quickly progress to become efficient readers, and may continue to slowly sound out words, especially when clues are not readily available.

So how do we teach a child to apply orthographic mapping to learn the many complex words of our language? It’s actually less complicated than it may seem. We start by showing children how sounds link to letters in simple words (phoneme-grapheme mapping), but we don’t need to teach a child to map every single word. Once children have grasped the concept of mapping sounds to letters, something brilliant then happens: they do it on their own for new words! Orthographic mapping results from the prerequisite skills of hearing the sounds within words and having a good grasp of letter-sounds correspondences. Typically, children encounter a new word, figure it out, and then after only a few exposures to the word, it is “mapped” and will be quickly recognized on subsequent encounters. This may seem surprising, but as David Share pointed out in his 1995 paper first describing his self-teaching hypothesis, there’s basically no other way. How else can kids learn to read so many words so quickly? Young kids typically learn to read in just a few years, so there would simply be no time to cram all the words in, if it were the case that many exposures were needed to learn to quickly recognize words.

But is English spelling actually too complicated to be learned this way? It’s true that English has one of the more complex writing systems, but it’s still an alphabetic (that is, sound-based) orthography. Speech sounds are represented by letters, just not in a 1-to-1 correspondence. For example, there are many ways to write the sound /f/ (fun, cough, stuff, phone), and there are many ways to pronounce the letters <ough> (though, thought, through). Due to the complexity, lots of people over the years thought that written English was simply too complex to learn through focusing primarily on the letter-sound relationships, and this is why we often see lists of “sight words” that students in early elementary must memorize, often as unanalyzed whole units. However, it turns out that even irregular words can be efficiently acquired through orthographic mapping. This is because: a) the majority of irregular words have only one or two unusual letter-sound correspondences and b) even unusual spellings can be anchored to sounds, if a child has good phonemic awareness.

Take the example “said” above. A child links the letters “s” and the “d” to their sounds, no problem. But it is very unusual for “ai” to link to the sound that is normally spelled with an “e” (as in “bed”) or sometimes “ea” (as in “bread”). Even though this is an uncommon link, we can still apply orthographic mapping. So, to help students learn the word “said,” we can explain, “Do you hear the “eh” sound? See how we write it with the letters “A-I” in this word!” Compared to learning the word as a whole visual unit (“take a mental picture of the word”), or by rote memorization (“S-A-I-D spells ‘said’”), this approach promotes orthographic mapping and more efficiently leads to instant word recognition.

Orthographic mapping is enabled by phonemic awareness and grapheme-phoneme (letter-sound) knowledge.

Ehri, 2014

So, when a child is good at orthographic mapping, they begin “self-teaching” new words, and are well on their way to becoming a great reader. For a child at this stage of reading acquisition, a great way to continue gaining skill is simply to read a lot. The more you read, the better you get at reading. Unfortunately, this is not so true for children who are not yet good at orthographic mapping. These are students who seem like they are encountering a word for the first time, even if it’s a word they’ve seen many times before, maybe even as recently as in the previous sentence. In this case, simply increasing the volume of reading (a “practice makes perfect” approach) will not help very much. On the contrary, requiring a struggling reader to just buckle down and read more is almost guaranteed to lead to frustration that can be so significant that it causes the student to disengage from learning to read.

What does help is pinpointing and addressing the underlying difficulties. We must assess the child’s phonemic awareness skills, letter-sound knowledge, decoding abilities, and ideally a few other skills. David Kilpatrick has discussed this in his book Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties (2015). He points out that in order to become a good orthographic mapper, a child must have very strong phonemic awareness skills. That is, it’s not sufficient to be able to slowly blend sounds into words (as in slowly figuring out that “f… + l… + a… + t = flat”), or segment words into sounds (slowly figure out that “spill = s + p + i + l”). Rather, students should be able to easily blend and segment sounds in words.

Kilpatrick theorizes that a good way to achieve proficient phonemic awareness is by incorporating phoneme manipulation, which involves changing the sounds in words, by adding, deleting, or substituting sounds.

Some examples of phonemic manipulation tasks:

- Deletion: Say farm. Say it again, but don’t say fff. (arm)

- Changing: Say shop. Say it again, but change the shh to hh. (hop)

Does it still seem a little strange to work on reading by doing auditory tasks? It can be an effective strategy when difficulty with phonemic awareness is a barrier to orthographic mapping. Importantly, though, phonemic awareness would be just part of the plan to help a struggling reader. We would also need to work on other skills such as: phonics (up to more advanced phonics, as in the trigraph “igh”— high, sight, mighty), morphology (learning word-parts, as in in-de-struct-ible), and vocabulary development. And, of course, we need to apply newly learned skills to writing and reading in context

I hope this post has been helpful in showing how the concepts of orthographic mapping, phonemic awareness, and self-teaching are crucial, if we want to help readers who struggle to efficiently recognize words. There is a sea of information available to help us find evidence-based strategies for efficiently helping all children reach their potential and become skilled readers, but the trick is making sense of it all! As always, if you have any questions or comments, I’d be thrilled to discuss. Leave a comment below or contact me!

References:

- Ehri, L. C. (1998). Research on Learning to Read and Spell: A Personal-Historical Perspective. Scientific Studies of Reading, 2(2), 97-114. doi:10.1207/s1532799xssr0202_1

- Ehri, L. C. (2013). Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5-21. doi:10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55(2), 151-218. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(94)00645-2

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643-662. doi:10.1037/h0054651

I’ve had writing a blog post on orthographic mapping on my to do list forever. I’m a big fan of Dr. Kilpatrick’s work and use it in my practice regularly. Will share your post today!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a fantastic article and you explain what orthographic mapping in such an straightforward way!

LikeLike

This article was so useful. I couldn’t get the video to work but gained a lot from the content. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person